By Evan Young | August 27, 2025

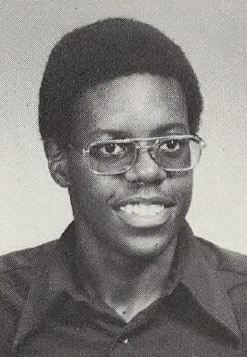

Twenty-five years ago, Willie A. Noble, BS ’79, gave back to WashU in an unconventional but nevertheless profound way.

Noble and his family moved from Atlanta to St. Louis so the civil engineer could become deputy project director for the MetroLink light rail system’s expansion from Forest Park to Shrewsbury. The project would take the MetroLink right by WashU’s Danforth Campus, and as an alumnus, Noble became the agency’s liaison to the university.

“I’ll never forget the first meeting with representatives from WashU,” Noble says. “When I introduced myself, I said I was a graduate of Washington University, and the staff representative said, ‘Oh, you’re one of us, then.’ They were proud of the fact that one of their graduates was leading the project.”

His involvement helped ensure the main campus received not one but two MetroLink stops along Forest Park Parkway: one at Skinker Boulevard and the other at Big Bend Boulevard. Combined with an additional stop on Forsyth Boulevard near the university’s West Campus, the MetroLink expansion marked the beginning of a new era of convenience and connectivity for the WashU community.

Engineering a passion

Noble traces his interest in engineering back to his childhood in Little Rock, Arkansas. It all started with a toy. His parents bought him an Erector Set one Christmas, which he would use to construct buildings.

Shortly before graduating from high school with honors, Noble received a letter from WashU inviting him to apply. He showed it to his guidance counselor.

“To be honest, at the time I hadn’t even heard of WashU. I was like, is this in the state of Washington? Is this in D.C.?” he says. “When I showed my guidance counselor the letter, he got excited. He said, ‘Washington University? That’s a great school. It’s in St. Louis, and that would be perfect for you.’”

Noble was accepted and received a generous financial aid offer, which helped him decide to attend.

“It meant a lot because my parents could not afford to send me to college, so I knew that the only way I would go would be by scholarship,” Noble says. “WashU ended up giving me one of the best packages, where it was more scholarships and fewer loans.”

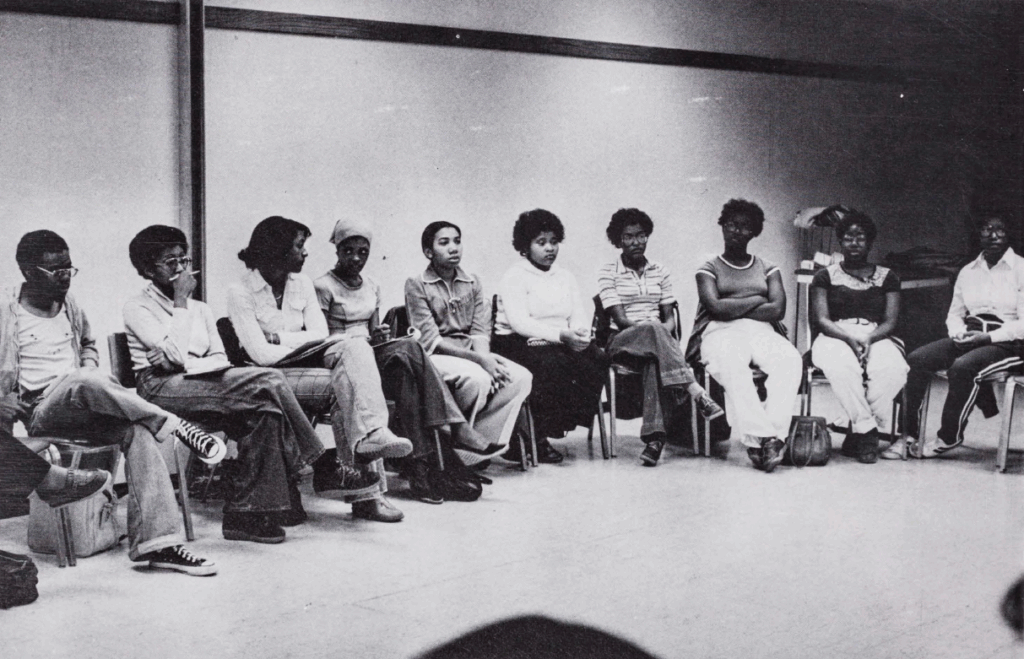

At WashU, Noble studied civil engineering with a concentration in structural engineering. He found fulfillment in courses both inside and outside of his major, from a steel design class taught by Dr. Theodore V. Galambos, his adviser and civil engineering department chair, to Black Psychology, an elective in Arts & Sciences.

“It helped me crystallize in my mind the importance of what Black Americans have experienced as minorities in the United States, from slavery to freedom and civil rights,” he says of the latter course. “It made me prouder of our accomplishments.”

After graduation, Noble worked for several companies as a structural engineer. He soon discovered WashU’s reputation extended far beyond academia.

“The various engineering companies I worked for respected the fact that I was a graduate of WashU,” Noble says. “It certainly helped advance my career.”

Noble eventually got into engineering management and in the early 1990s joined the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) to manage the team responsible for maintaining existing structures, such as bridges and tunnels. It was his first foray into public transit, and he would remain in the field for the rest of his career.

A WashU homecoming

When Noble returned to St. Louis in 2000 to work for Metro Transit on the eight-mile MetroLink expansion, he was placed in charge of 24 agency employees overseeing a design joint venture known as the Cross County Collaborative, who were hired to design the project.

The project had gone through conceptual design, and Noble took the plan on the road to public meetings with residents and businesses along the proposed route. While the two Danforth Campus stops were part of the initial design, Noble had to advocate keeping them both in the final plan.

“I recall that as the cost was increasing, there was discussion within Metro of only providing WashU with one of those two stations,” Noble says. “I didn’t agree with that and argued against it, and the university officials also opposed it when it was brought up in my meetings with them. Together we were able to convince the agency to keep both of those stations.”

Noble also helped obtain Metro buy-in for WashU’s idea to include a pedestrian bridge over Forest Park Parkway to the adjoining Parkview neighborhood. The bridge was designed to be functional and a “thing of beauty,” Noble says, as the university wanted it to complement the architectural style of the Danforth Campus.

“I saw my role on the project not only as overseeing the design process and watching the cost and the schedule but also representing my alma mater as best as I could and making sure that the design served the university’s interest as well as possible,” Noble says.

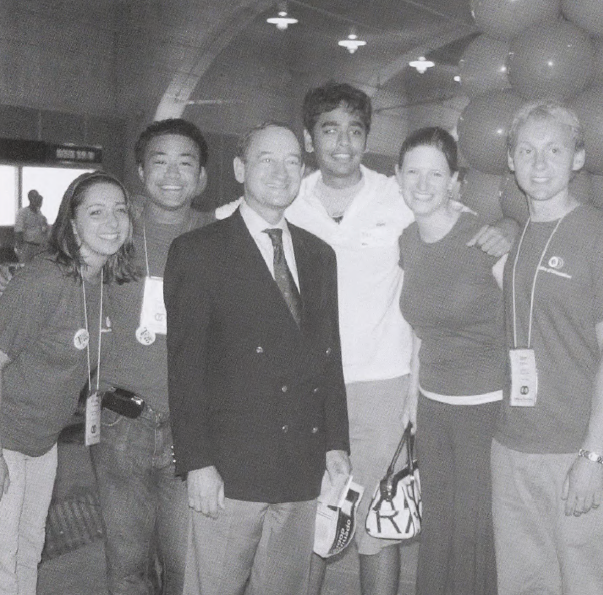

Despite delays and cost overruns, the MetroLink expansion opened on Aug. 26, 2006, to much fanfare. WashU’s then-Chancellor Mark S. Wrighton heralded the new stops as a “tremendous resource for our faculty, students, and staff.” With the existing Central West End stop serving the WashU School of Medicine, the university community and visitors could now travel between three campuses exclusively by light rail. Though he left Metro in 2004 following completion of the design phase, Noble says he’s been able to ride the alignment he helped create several times.

Noble continued to work for transit agencies and consultancies until he retired in 2023. During that time, he and his wife, Rosilynn, assumed yet another WashU role: parent. Their daughter, Alexia, earned her law degree from the university in 2015.

“When she told me that she had decided to go to WashU, I admit that I had a swell of pride,” Noble says. “While she was there, it took my respect for WashU to a different level, and it was capped off by sitting in the Quad for her graduation. I never thought I’d be attending another WashU graduation, but as I was sitting there, I was just so full of pride that my daughter and I ended up being alumni of the same institution.”

Related stories

Powered by design, anchored in community

Angelyn Chandler, AB ’89, has built a powerful career in public-sector architecture, shaped by her fascination with urban life and her passion for New York.

Victorious spirit

Alumnus Bert Mandelbaum has seen the best of humanity throughout his long sports medicine career.